More than half of the global population currently lives in cities, with an increasing trend for further urbanization.

Houses are becoming less affordable. According to Zumper’s most recent national rent report, the price of one bedroom in New York City is $2,900, with two bedrooms growing 1.7% to $3,500. Living in cities also mess up people’s mental health. Research shows that people living in cities have a 21% increased risk of anxiety disorders and a 39% increased risk of mood disorders. In addition, the incidence of schizophrenia is twice as high in those born and brought up in cities. Moreover, in my personal experience as an international student, I found a lot of my friends experiencing homesickness, loneliness, and a very high level of pressure during their time far away from home. Therefore, I started this research seeking ways to help with city people’s mental disorders.

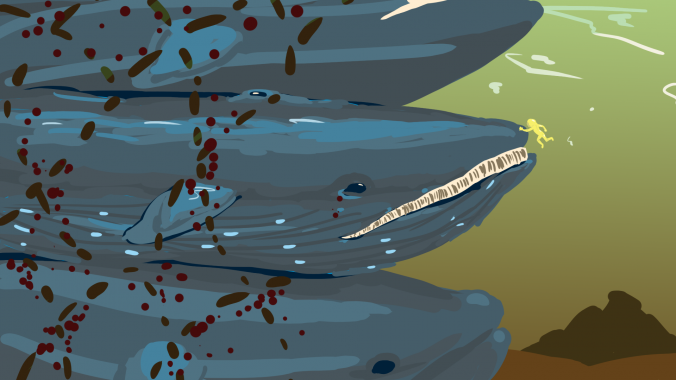

The idea came from Japanese animal cafes, where customers can play with resident animals while having a cup of coffee. “People today are under a lot of stress,” said Masayuki Takamatsu, board chairman at the Nihon Animal Therapy Association. “It has been proven in neuroscience that humans feel better after spending time with animals they like.” Seeing how popular animal cafes have become in Japan, I decided to focus my research on increasing the impact of animals (pets) on city people’s mental disorders.

Differing from the living situations in Japan, American apartments are a lot bigger in general. So rather than going to animal cafes, more people keep pets in their houses. Among my friends, a lot of them own a cat, a few own a dog, and even fewer own small animals like rabbits or guinea pigs. In order to get more users and testers, I chose to design the first product for cats and cat owners.

I interviewed my friends who own cats and observed them in their home environments, paying particular attention to the interactions between the owners and their cats, the products they use, and the environment itself. I saw that cats were rather clingy creatures. Besides sleeping and playing with cat toys, they love trying to get their owners’ attention. Among the five cats I observed, two of them love stepping and sitting on the laptop when my friends were trying to do work. “I love having Luna around my desk, even if sometimes she disturbs me a little,” said Chun Wang. “Usually she will just go back to sleep after me playing with her for a while. If she gets too excited, I’ll put a little box on the table and she’ll sleep in the box. Few cats can say no to little boxes.”

In Troy, New York (the location of my research & current home), the average size for an apartment is 1,047 square feet – which is enough for a party of two people and a cat – but even so, is still a bit crowded for most parties I interviewed. To optimally design for city people and their cats, I tried my best to minimize space usage while letting the cat keep their owner’s company as much as possible. Having that goal in mind, I sketched a student desk with a sunken area for cats to sleep in.

The shape and depth of the cat’s desk area are still being tested, and, based on user feedback, other functions might be added in the future.

While our users are testing the desk, we are trying to start designing our second product – which might be a hiking bottle for dogs. Keep an eye out if you’re interested! We are also constantly looking for cat owners to help with user testing, so please let me know if you are willing to help! Thank you:)

Jiawen Liu (Alice) is an Electrical Engineering and Design Innovation and Society major – interested in industrial design, theme park design, cultural anthropology, and filmmaking. Hobbies: traveling, road biking, being with animals, daydreaming… Favorite color: sky blue. Favorite food: chicken wings. Favorite animation: Spirited Away. Currently working on the project WithU – which seeks ways to increase the positive impact of animals on human mental illnesses through products.

References:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5374256/

https://www.zumper.com/blog/2018/04/mapping-new-york-city-neighborhood-rent-prices-this-spring-2018/

https://www.theguardian.com/science/2011/jun/22/city-living-afffects-brain

https://www.rentcafe.com/average-rent-market-trends/us/ny/troy/